Tell Me About Your Lake (and Other Market Analysis Analogies)

Markets are such a nebulous thing. Markets can feel like yet another business term (YABT™) that tries to objectively categorize something as subjective as “demand” or “people’s problems”. But that doesn’t mean it’s not an incredibly important concept! In fact, thinking in terms of markets has probably been one of the most important skills I learned early in my career. The problem with the word “market” being such a vague term is that people talk about markets with reckless imprecision.

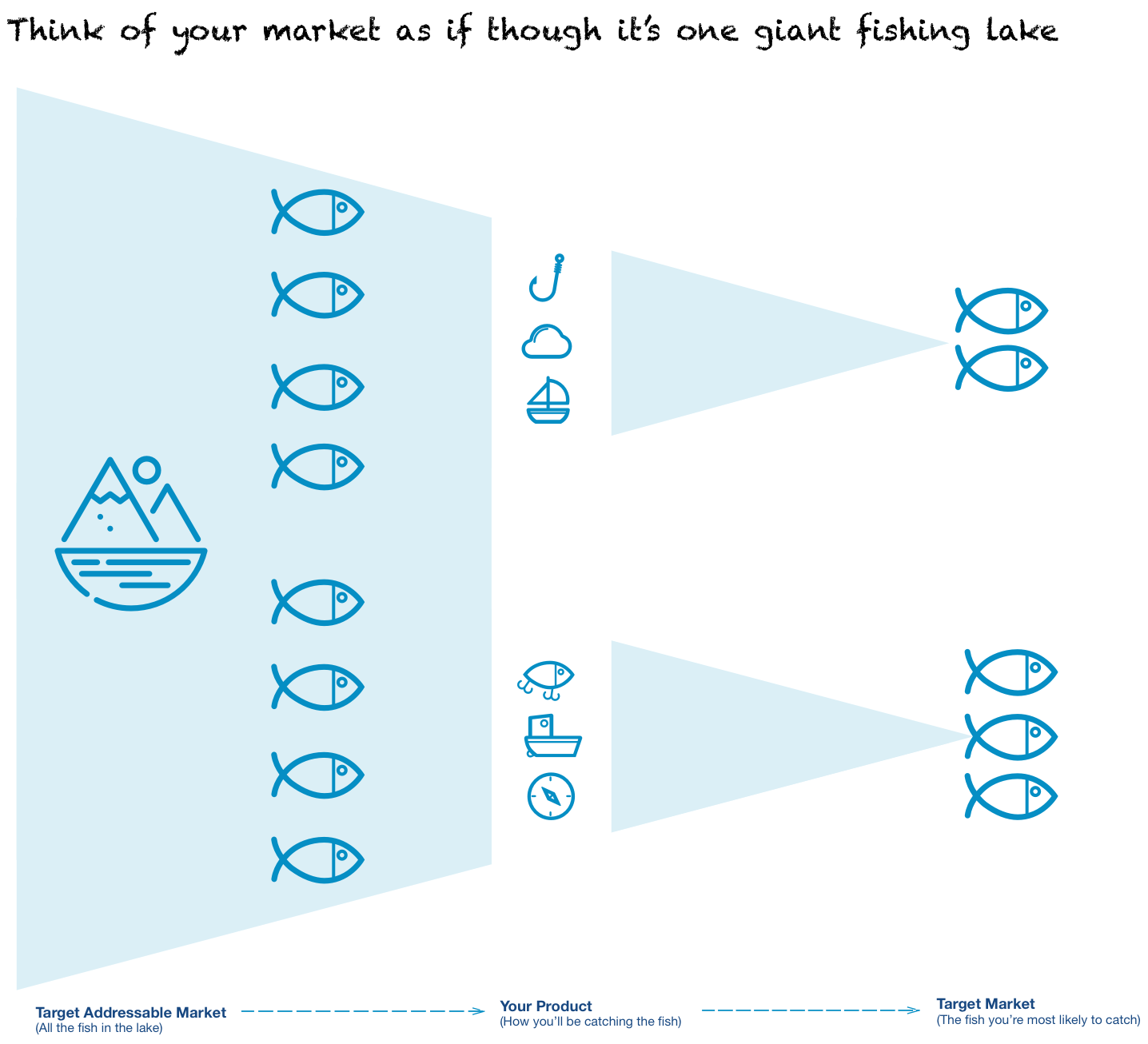

Often my students would struggle to think in terms of markets - they found the concept daunting and unfamiliar - so instead, I encourage them to think and talk about their market as if though it was a fishing lake. Markets are vague - lakes are crystal clear!

I love asking this question to an entrepreneur: “tell me about your lake”. To me (and hopefully to them) their lake is more important than how they’ve decided to go about fishing from the lake.

- How big is the lake?

- What are the fish like?

- How do I get there?

- Who else fishes there?

- Why haven’t more people found this lake?

When people talk about their market in terms of a lake, it’s easier for everyone involved and gets everyone on the same page. Now when someone says market, everyone clearly pictures a place where there is a limited amount of fish(buyers) for people to catch.

Give me a giant market — always. My position has always been: you find a great market and you build multiple companies in that market. Our view has always, preferably, been: give us a technical problem, give us a big market when that technical problem is solved so we can sell lots and lots and lots of stuff. Do I like to do that with terrific people? Sure. Are we unwilling to invest in companies that don’t have them? Sure. We invested in Apple when Steve Jobs was about eighteen or nineteen years old — not only didn’t he go to Harvard Business School, he didn’t go to any school. — Don Valentine

Where new excited entrepreneurs get confused is when they think “demand” is the “market”. Demand, by itself, does not make a market: people wanting to pay money to solve a problem is an indication there may be a market, but markets should be massive. Invest in big markets first (always) and then build a company (or two) around that market.

Here’s an example: your new fledgling product is beginning to grow. You’ve got 20 or so happy customers, all paying to use your minimum viable product and you’re signing up about 1 new customer per day from word-of-mouth alone. Are you onto something big? Is it time to quit your day job and hire some developers? Stop! Wait a second! Tell me about your lake. We’ve all gone fishing before and caught some fish, but that doesn’t mean we’re going to pack up everything and move to the lake for a few years because the lake is clearly such a lucrative opportunity! You better be very certain that the lake you want to be fishing from (for a few years) is big enough and worth the commitment. To be clear: you’re not interested in catching 20 fish - that’s easy - you’re interested in catching thousands or millions of fish. Once you’ve found and analyzed your lake (size, number of fish, etc), then it’s just a matter of getting better at fishing from the lake (different approaches, more fisherman, new lures, etc).

Your Lake (Market Analysis Basics)

Rule: You are never allowed to talk about your market vaguely or imprecisely. Yes, markets can be inexact, but not yours! You grok (verb: to understand something deeply, appreciate actively and profoundly) your market because you’ve defined it in one of the most detailed (and probably quite expensive) spreadsheets you’ve ever put together.

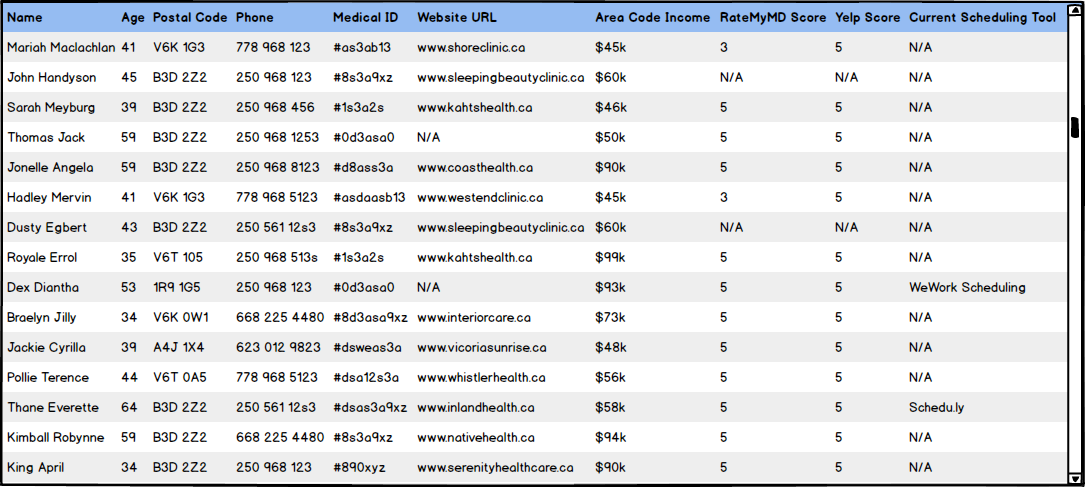

In this example, let’s pretend that I’m building a scheduling app for family doctors. OK, even though I could sell (or fish) anywhere in the world, the reality is, we all have to start selling (fishing) in one location. So for now, let’s say I’m going to start selling in British Columbia, Canada. How many GPs are there in BC? Well, I could estimate the total number of doctors quite accurately using various estimation techniques, but luckily the BC Government has a directory of physicians which I can programmatically/painstakingly scrape to get the complete list. The total was around ~5500 family doctors. So that’s the size of my lake. There are 5500 fish that I could catch.

Next, we want to get as much relevant information about each doctor on that list. My assumption is that young family doctors, with a professional website, in high-income areas are more likely to buy from me. In addition, my other hypothesis is that any doctor that’s using a scheduling tool may be inclined to buy from me since they’ve had a terrible experience with their existing/legacy scheduling tool. All of these individual data points take time to research, but it is possible. Here’s how I’d do it: I can use the BC census data to determine the average income by postal code. I could use a tool like Built With to determine which (if any) scheduling tool is running on a family doctor’s website. You can also retrieve Yelp or other review scores to determine the customer friendliness of their clinic. You could put up a Craigslist ad and offer to pay someone $100 if they go through the list and mark everyone they think comes from Austria, Germany or Switzerland (where healthcare is of a very high quality and therefor they’d be more inclined to buy from me). Money spent doing this upfront research is much less expensive than any kind of engineering work.

“In the early days of a product, don’t focus on making it robust. Find product market fit first, then harden” — Jeff Lawson

How Hungry are the Fish? (defining your target market)

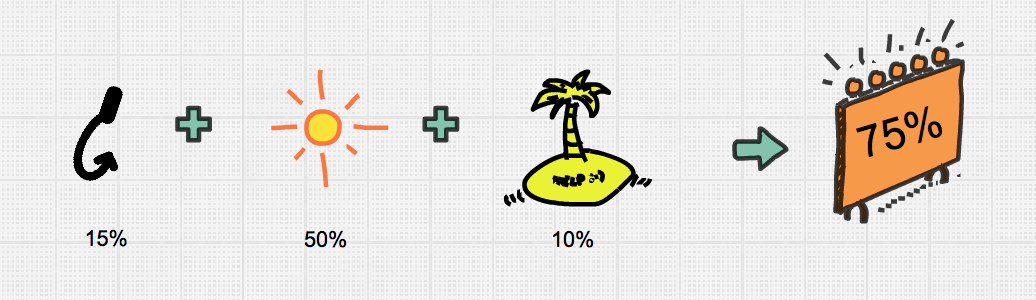

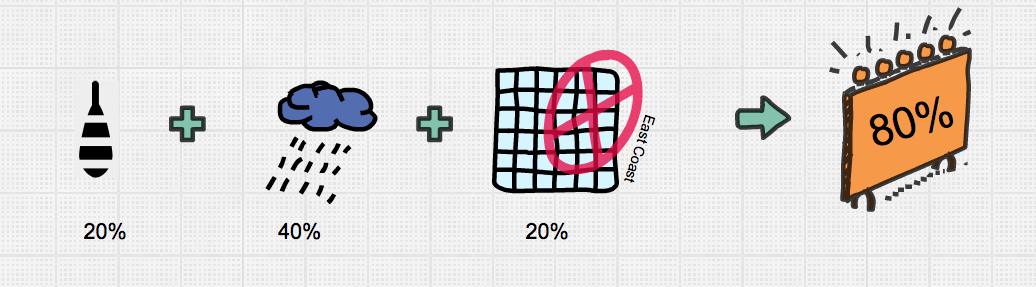

If you’ve ever gone fishing at a remote lake you’ll know that there’s always a trick (or two) that the locals are willing to share on how to best catch fish at that specific lake. Maybe it’s sparkly fishing lures in the morning on the east bank, fly-fishing at sunset on any shallow beach or maybe try using a floater for catching bigger fish from your boat. All of these methods of catching fish work, but we should go about trying to identify and score each method to estimate how many fish we expect to catch using the various techniques and criteria available to us. We want to give each fish/doctor/prospect a score out 100 to determine the likelihood they’d buy from us given the criteria we’ve identified. The simplest way to do this is to list each criteria and give them a score that they contribute to the overall number or you can create more complex ways of scoring the list of candidates.

Here are 2 fishing tips we got from the locals:

- Fishing in daylight near shallow beaches

- Use floaters when it’s raining outside but stay on the east coast

Ok, now what about doing the same thing but with our list of doctors? Below is a very simple example where we’re adding up values one after another - but, if we wanted, it could be much more complex and intricate. For example: we can make it so that if the doctor does not have a website then we will automatically give them a score of 5% overall (because they can’t buy our online scheduling app anyway then). It helps to circulate the list of criteria to around 5-7 people who know the market well and ask them what percentages they might give each criteria (and ask them why they think your suggestions were too high or too low). This will ensure your numbers/percentages are supported by a few more people’s experienced opinion.

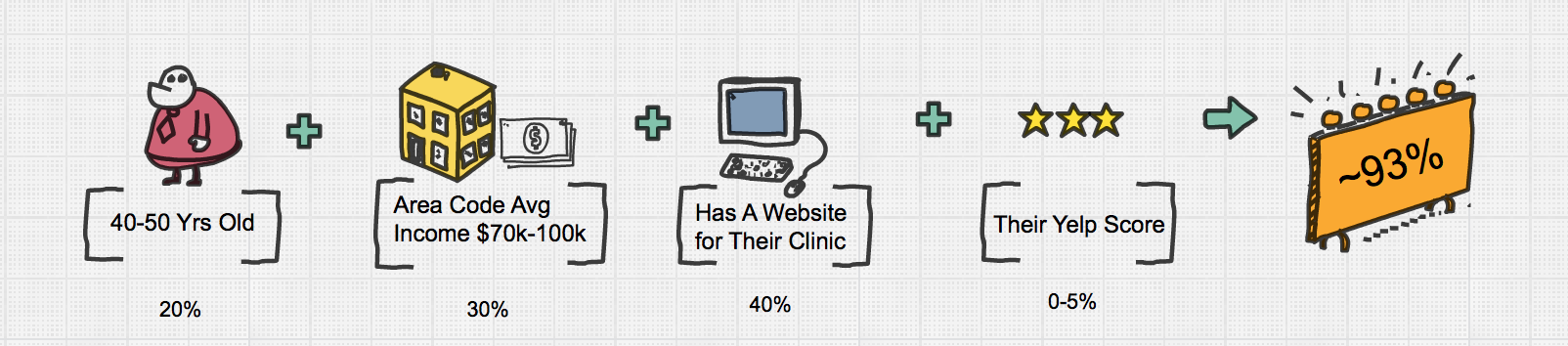

Here’s a very simple illustration on how we give a doctor a score of 93 / 100:

If we wanted, we could’ve created a much more complex (and hopefully more accurate) method. It really depends on how detailed you want to get, and how well you know the criteria you’ve identified as being important. Next, let ’s calculate the score of every doctor. Remember, the higher the score, the more likely we think they are to buy from us.

- Scores between 85-100% are on the “they would be stupid not buy from us” list.

- Scores between 75-85% are also very good candidates and will most likely be won-over with a few minor tweaks here and there.

Typically, I’ve found these two brackets of customer segments are the biggest contributor to my new products financial break-even point (more on this in a later article).

“Founders have to choose a market long before they have any idea whether they will reach product/market fit.” — Chris Dixon

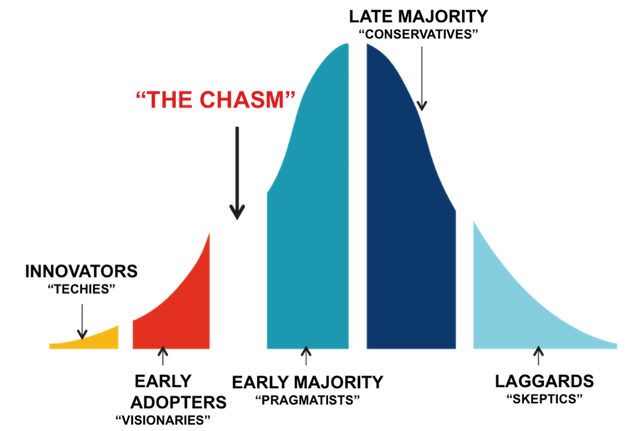

Ok, so if the green and yellow sections (shown above) usually get us our money back (to break-even), then how do we sell to everyone that’s left? Ah, yes, good question! There’s a book written about this very dilemma called Crossing The Chasm. Simply put, you’ve just discovered why it’s easy to get the Innovators (green) and Early Adopters (yellow) and now you’re wondering “how do I cross the chasm” and catch the rest of the fish in my lake. I highly recommend reading Crossing The Chasm to not only understand that 1) this is a very normal problem almost everyone faces in new product development and 2) crossing the chasm is like the Oregan Trail of startups: special arrangements need to made, it’s expensive and you might lose a few people on the way.

So Long and Thanks For All The Fish (and what’s next?)

In the next article, I’d like to continue the analogy of using a lake to determine your initial product investment (and your estimated return). Also, if you’ve found a nice lake, then you can’t keep it a secret forever. Sooner or later other people will begin to show up and take home some fish of their own. Naturally, the lake will run out but few people anticipate and correct for this (not identifying a lake that was about to run dry has been the costliest mistake in my business career and I’d like to share that in another upcoming article). I hope you’ve found the lake analogie useful and I hope it encourages you to think in terms of “markets” more often and that you challenge people to be more precise when they discuss markets with you.

You can expect more lake-related analogies from me in the future (and next time I’ll try to include more dam puns).